Cambodia is both a beautiful and tumultuous country. From the floating villages on Tonle Sap Lake, through bat caves and rice fields, to the mysterious and stunning Angkor Wat. Finally, you might even end up “where the pepper grows”—since the country is famous for its pepper cultivation.

Cambodia still bears the scars of its civil war. It’s also well-known for the grim history of the Khmer Rouge regime. Once a shining jewel of Asia, decades of conflict and unrest have left it a very poor nation. Only recently has peace begun to take hold. Despite fresh wounds and lingering scars from the wars, the local people strive to maintain a cheerful spirit, though they often remain cautious around strangers.

You should definitely mention Phnom Penh, the capital of the country. Although we haven’t yet had the pleasure of visiting it, there’s always next time! Phnom Penh is a rapidly developing city where wealth and poverty intertwine.

Need to Know: How to Get There

Entry Requirements:

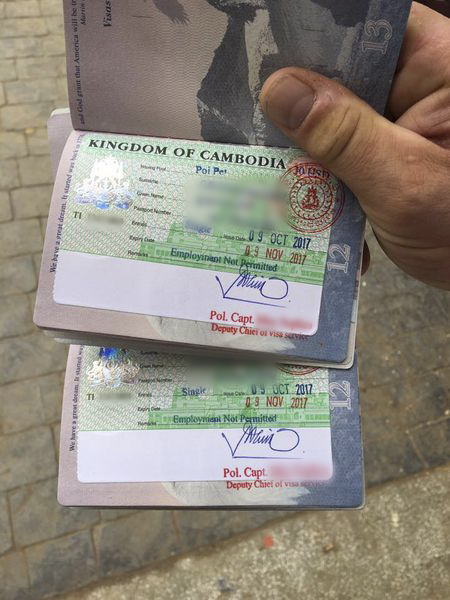

To enter Cambodia, you will need a visa, which can be obtained at any border crossing.

- Cost: $37 ($30 for the visa and a $7 administrative fee).

Transportation:

The nearest city to Angkor Wat is Siem Reap, which is just a few minutes away from the temple complex.

The road network is well-developed, so you’ll have no trouble getting there by bus or tuk-tuk.

- Bus fare: From Phnom Penh to Angkor Wat, tickets cost about $15. From Poipet, around $11.

- Private car hire: A private car from either city costs between $60 and $120. Visit local agencies, ask around, and bargain! Negotiating will always work to your advantage.

For more information about bus routes, check this link:

12go.asia – Bus Routes from Phnom Penh to Angkor Wat.

Admission Tickets

- A one-day ticket currently costs $37.

- If you plan to stay longer, consider a three-day pass for $62 or a seven-day pass for $72.

Food

Rice is the staple food in Cambodia. The Khmer saying for “let’s eat” is “nam bai,” which literally translates to “let’s eat rice.”

You must try:

- Beef with red tree ants

- Khmer Red Curry

- The delicious soup, Samlor Korko.

Fried or roasted insects are also very popular here, as in many parts of Asia.

If you’re a fan of McDonald’s, you’ll go hungry in Cambodia. However, if you enjoy culinary experiments, you’ll find that Khmer cuisine differs significantly from Thai food.

Food Prices:

Food in Cambodia is very affordable by our standards. However, remember to bargain if prices aren’t listed on the menu or confirm the cost beforehand—it could end up being as pricey as a meal at the Ritz!

Must-Have Essentials

When traveling in Cambodia, there are a few essential things to keep in mind:

- Cash: Always carry enough cash with you. In most poorer countries, including Cambodia, credit card payments are rare.

- Clothing:

- Wear bright colors: Light colors contrast beautifully with the gray and orange stone backgrounds.

- Cover your shoulders and knees: Avoid wearing tank tops, short skirts, or shorts. Long skirts and maxi dresses are acceptable if they cover your knees.

- Dress modestly: Avoid revealing clothing.

- Wear comfortable clothing: Choose breathable, lightweight outfits suitable for walking and being under the sun.

- Choose comfortable footwear: Sneakers or trekking sandals are ideal for walking and climbing stairs.

- Bring leggings: If you plan to wear a long skirt with slits, leggings might be a good idea.

- Remove shoes and headgear: Take off your shoes, sandals, and hats before entering sacred sites.

Angkor Wat

Our trip to Cambodia was unplanned, as is often the case with us, and done “on the go.” You’ll probably notice that we rarely have concrete travel plans, and even when we do, they quickly change. This time was no different.

We were visiting Thailand for the second time (we love that country for its culture, people, and, of course, the phenomenal food). You might wonder why we went there twice. Well, it’s an interesting story.

For our honeymoon, we planned to go to Bali. We were thrilled, not only because it was our honeymoon but also because we had both always wanted to visit Bali. Everything was prepared to perfection, but then—surprise! A series of earthquakes struck Bali, triggering a volcanic eruption.

We held out hope, thinking it might just be a warning tremor, but the worst-case scenario came true. Just two days before our departure, authorities announced the evacuation of the island. So, what now? After a long deliberation, my wife Brydzia and I decided that Thailand would be the perfect alternative. We changed our tickets to Bangkok and set off.

Upon arriving in Thailand, we rented a car and hit the road. In Thailand, as in many former British colonies, you drive on the left, so we had to adapt quickly. Surprisingly, despite the chaos, driving was fairly smooth. Leaving Bangkok, we headed east on Route 304.

About 2.5 hours into the drive, we turned right onto Route 359, which leads to the Cambodian border. By nightfall, we arrived in the small border town of Aranyaprathet. It was dark, the streets were deserted, and locals had retreated into their homes. There was no one to ask for directions to the border crossing.

Finally, we spotted two uniformed Thai officers on a motorcycle. They must be border guards! Taking a chance, we followed them. Bingo! We found the border crossing. Or did we? It was dark and completely deserted. The border was closed.

Why was it closed? When would it reopen? These questions filled our heads, but there were no answers in sight.

We stood there wondering, “What now?” It felt like a dead end. Luckily, the men on the scooter—aside from tuk-tuks, scooters are a favorite mode of transportation in Asia—turned out to be border employees. One of them, purely by chance, had returned to retrieve his phone.

We were even luckier when we realized that one of the guards spoke decent English (and here I’m being very generous with the word “decent”). He explained that the border is open only from 6:00 AM to 10:00 PM, seven days a week.

So, we were faced with an unexpected stop. It was the middle of the night, everything was closed, and darkness surrounded us. What now? It was time to live by the Marine Corps motto: “Improvise, adapt, and overcome.” Time to refine our plan.

We had an “emergency” stash of food, so at least we didn’t need to worry about that. The next issue was accommodation. One option was to spend the night in the car—though that wasn’t our preferred choice. Thankfully, the border staff, who were very friendly (you’ll notice how kind and polite people in Thailand are when you visit), guided us to the nearest hotel. They even woke up the owner before leaving.

Before booking a room, I went to check it out. How can I describe it? Well, the room was modest but clean. The once-white bed sheets had aged to a shade closer to ivory, but they were tidy. It wasn’t the Hilton, but we’ve slept in worse places. The owner also showed me the shared bathroom for the entire floor. That was the deal-breaker.

Shared bathrooms don’t bother us—after all, it’s standard in hostels—but this one featured a hole in the floor that served as both a shower drain and a toilet. We couldn’t quite bring ourselves to embrace that experience. But hey, different countries, different customs.

We managed to find an internet connection and, using Kayak.com, booked a lovely, cozy hotel called Hey Sunday Home. It came with a private bathroom and—importantly—a toilet separate from the shower. The hotel itself was charming and had a welcoming atmosphere. If you’re early enough, you can even relax in their atmospheric garden during sunset.

The location was also excellent, offering privacy away from the hustle and bustle while still close to all the attractions.

Aranyaprathet has a few modern hotels, but availability is limited, so it’s wise to book in advance if you can. We were just lucky.

After a comfortable night’s sleep in clean sheets, we headed to the border early the next morning. Everything went smoothly—until we learned we couldn’t cross the border with our car. This didn’t bother or frustrate us. We simply made a U-turn and returned to the hotel.

We asked the staff if we could leave our car in the parking lot for a day. They had no issue with that. While there, we also booked another night since we’d need to come back for the car—and after a full day, we’d need some rest.

With that sorted, we set out for the border on foot.

On the way, we passed long lines of people heading back from the border. It turned out that many Cambodians work in Thailand due to better wages and opportunities. In the other direction, we saw food products being transported. At one point, a large cart lost a wheel, spilling fish all over the road. The locals quickly banded together to fix the cart and reload the goods—straight from the street!

Border Crossing

Right by the border is the Talat Rong Kluea Market. It’s worth a visit, but be mindful of your personal belongings. Cambodians, like Thais, believe in karma, but poverty often overrides religion. In crowded or tourist-heavy areas, your wallet might quickly find a new owner.

As soon as we entered the local market, we were approached by local “handlers.” Understandable, really—my muscular build stands out, and a 175 cm tall blonde woman is hard to miss in a crowd averaging 150 cm in height.

These “specialists” offer all sorts of services, but primarily assistance in crossing the border. We were surprised by how fluent many of them were in English. To the point—these “tour guides/visa advisors” promise to secure a visa for you for $100 per person. Yes, even U.S. citizens require a visa to enter the Kingdom of Cambodia.

What amused us even more was when one of the men asked us to hand over our passports and wait for him right there. I almost burst out laughing. Sure, we’re tourists, but we’re not idiots. However, I have to admit this tactic must have worked before; otherwise, they wouldn’t have asked.

Naturally, we refused and told him we’d take the visas, but I would accompany him to the service counter.

While wandering around Talat Rong Kluea Market, it became obvious that the man was scanning the crowd, looking for someone. My professional instincts kicked in, and something didn’t feel right. It seemed like a setup to scam tourists. Before our “visa helper” realized it, I was gone.

I returned to Brydzia, who was waiting at the crossing. In the meantime, she had asked around and discovered that getting a visa wasn’t an issue. We crossed the border into Cambodia, ending up in the city of Poipet.

At the immigration office, we filled out visa application forms and paid the fee.

- The visa cost: $30

- Administrative fee: $7

- Total: $37 per person, or $74 for the two of us.

I suspect that using the “market agency” would have been a far more expensive experience—$200 for visas and no passports to show for it. So don’t fall for their tricks!

Finally, we crossed the border and arrived in Poipet. From there, we still had a few hours to reach Angkor Wat.

We found a local taxi driver and hired him and his car for the day for $150. Soon, we were on our way.

The journey took us through tiny villages where local vendors called out to potential customers, and past rice fields, pepper plantations, and banana crops. The contrast between the vibrant market scenes and the tranquil countryside was mesmerizing.

Halfway through our journey, we stopped at a local eatery for a well-deserved meal. As is typical for us, the more local the spot, the better. We ordered soups and something that looked like chicken. The owner of the establishment served our dishes, and we began sampling the local cuisine. What delicacies they were (cue sarcasm). As a seasoned veteran, I’ve eaten much stranger “delicacies,” so I couldn’t really complain. However, Brydzia… well, poor Brydzia had some trouble with the poultry, which was not entirely free of feathers or claws. Nevertheless, the friendly atmosphere made up for the differences in our culinary tastes.

The rest of the journey was rather monotonous… though one incident caught our attention and stuck in our memories. As we passed a rice field, we saw an elderly man walking with a cow. There wouldn’t have been anything unusual about it, except for the fact that the man waded deeper and deeper into the water until only his head and a cigarette were visible above the surface. Remarkably, the cigarette survived the entire crossing—it didn’t even go out! As the man emerged from the water, he continued smoking as if nothing had happened. We waved at him with a friendly gesture, and he responded with a toothless smile.

We finally arrived at Angkor Wat. After purchasing tickets, we entered the complex. However, before crossing the city gates, we had to buy a shirt and pants for Brydzia, as her outfit was a bit too revealing…

The city is entered through five gates. Yes, you read that right—five, not four, as is customary in Asian culture. The fifth gate is called the Victory Gate, and it leads directly to the royal section. This is the gate through which the king would return to the city after a victorious battle. But we’ll come back to this gate later.

Before entering, you’ll encounter swarms of hawkers, vendors, and tour guides. Personally, we’re not big fans of tour guides, but this time, we let ourselves be convinced. Our guide was a man who had grown up in Angkor Wat. His story reflects the history of Cambodia itself. His parents were killed under the Khmer Rouge regime, and he was raised by Buddhist monks right there. As a child and young man, he had the chance to explore every corner of the city and uncover its secrets. Let me tell you—it was worth it. Not only did he guide us through the entire complex, but we also learned fascinating details that you’d typically only hear from local residents.

The city itself is monumental. Words cannot do it justice (maybe if I were Mark Twain, I’d stand a chance, haha), so take a look at the photos instead.

Imagine a thousand-year-old metropolis with a population of one million, covering an area of 3,000 square kilometers (741,316.1 acres)—that’s twice the size of New York City!

During our visit, we heard many stories about the construction of this complex and its transformation from Hinduism to Buddhism (a tradition it continues to follow today).

While every guide will tell you about the bas-reliefs adorning the walls of the complex, none will likely mention one very specific bas-relief. The entire complex features 1,737 depictions of Apsaras (originally a type of female spirit associated with clouds and waters, later considered nymphs or fairies), each one unique and unparalleled throughout the site. However, the most important one is a single figure smiling and showing her teeth.

This particular bas-relief is located on the opposite side of the road from the stone bridge, which served as the main (western) entrance to the Angkor Wat complex. It is almost hidden from view. Legend has it that it was placed there intentionally to symbolize the joy of the king’s return. How much truth there is to this… who can say?

Photo of the Apsara

While exploring the city, we came across Buddhist monks of all ages, from young boys to elderly men. They all treated each other with respect and love. We stopped to observe the monks as they prayed, taking a closer look at their rituals.

They invited us to join in their “prayer” and blessing. It is said that a monk’s bracelet brings luck and protection to the person who wears it. This bracelet is blessed by monks or other spiritually practicing individuals who imbue it with positive energy. This positive energy is believed to attract luck, abundance, and all good things into one’s life.

How could we possibly refuse such luck and protection?

Photo of us receiving a monk’s blessing.

After the ceremony, we continued our tour. I noticed that some of the stone blocks used in the construction had holes, while others did not. Curious, I asked our guide if this had a specific purpose—and I wasn’t wrong.

The materials for the entire complex were brought from quarries located 50 km away, but that didn’t fully explain my question. The stones were transported via a network of canals on rafts. However, during the dry season, this method was no longer possible—or so one might think. Not for the builders of Angkor Wat! They drilled holes in the stones so they could be transported by elephants.

But that’s not where the ingenuity of the builders ended. What was the purpose of placing the stones in such specific locations? Apart from ensuring a year-round water supply in the monsoon climate to support the population, agriculture, and livestock, the hydrological system also irrigated the sandy foundations, which allowed the temples to stand for centuries. Regular sandy soil cannot bear the weight of the stones, but the master engineers discovered that mixing sand with water creates a stable foundation. This is why the moats surrounding each temple were designed to provide a constant supply of groundwater.

Impressive, isn’t it? No engineering degrees, no building inspections—and yet look at their achievements! Meanwhile, our modern builders can take ten years to construct a 20-km highway, and it’s already in need of repairs before it’s even finished. Lol!

We were also intrigued by the towers, which are almost inseparable from the architecture, especially the way the stairs were built.

You’ll notice that the stairs are not all the same. Those at the bottom are wide and relatively low, making them easy to climb. However, the higher you go, the narrower and steeper the stairs become.

Why? The stairs lead to altars or sacrificial places for the “gods.” The design of the stairs carries two meanings. At the bottom, representing “hell” or “sin,” life is easier, so the stairs are wider and easier to climb. But the higher you go, the closer you are to the gods, and life according to their rules becomes more challenging—just as salvation is no easy feat.

There’s also a more practical reason: when sacrifices were offered on the steep, narrow stairs, people had to descend backward, keeping their heads turned upward. This ensured they didn’t turn their backs (or worse, their behinds) to the gods.

Our time was coming to an end, so we took a few final photos before heading back.

The return journey went much faster. By the time we reached the border, it was dark and a light rain was falling. The darkness, rain, and lingering scars of past conflicts created an eerie, almost horror-movie-like atmosphere. While we loved our time at Angkor Wat, at the border, we felt like prey being watched. To avoid tempting fate, we hurried toward the crossing.

Here, we had an encounter that I must tell you about. It has nothing to do with history or tourism, but it’s an episode that will stay with us for a long time.

First, let me tell you about a mother and son returning from Thailand. It was clear they weren’t wealthy, but they didn’t look destitute either. The boy was overjoyed with a toy he was pulling on a string—a small car. But this wasn’t a store-bought toy or something from Amazon Prime. It was a water bottle with wheels made of caps attached to wires. How little it takes to find happiness! His joy was so genuine.

And us? We compete to buy our children everything, but in truth, none of it holds much value for them—not the way this little car did. That boy held onto the string as if his life depended on it.

But it’s not about him I want to tell you.

As we crossed into Thailand, we saw a boy and a girl standing by the sidewalk. He was about ten, and she was only slightly younger. It was hard to tell. They were clearly living in poverty. The girl approached us—she was either very brave or very desperate. She wore what must have once been pajamas and was barefoot, dirty, and tangled-haired. The boy stayed at a distance, watching warily. On his forehead, he had a fresh wound, one that looked more deliberate than accidental.

As the girl came closer, she held out her tiny hand, silently asking for alms. (We noticed how people ignored her, walking past indifferently. Maybe decades of war and terror have stripped them of empathy and kindness? It’s hard to say.)

We didn’t have any coins because the exchange rate was (if I remember correctly) about 4,000 riel to $1. We still had tens of thousands of riel left, which we knew we wouldn’t use. The girl approached Brydzia, likely feeling safer with a woman, and smiled—a wide, hopeful smile that Brydzia returned.

Brydzia took the banknotes and placed them in her tiny hand. The explosion of joy that followed was unforgettable. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a child so happy. She squealed with excitement, so much so that she was out of breath. In her euphoria, she threw her arms around Brydzia’s neck, saying something in her language (likely a thank-you).

Seeing this, the boy finally dared to approach. He was hesitant, but when he saw his sister’s joy, he became more trusting. He received the second handful of banknotes. To us, they held little value, but we didn’t realize how much they meant to them.

After both children hugged Brydzia tightly, we had to leave. It was heartbreaking that we couldn’t help them more—and yet, we later learned something that put it all into perspective.

We hadn’t realized how far their money could stretch. What was worth about $30 to us was a fortune to them. We found out that an average family of four spends roughly $200 per month on food. Can you imagine that?

Shortly afterward, we crossed the border into Thailand and returned to our hotel.

no comment